Siobhain brought together a number of other MPs to call for the UK government not to turn its back on international participation in securing justice in Sri Lanka.

Back in 2013, the Prime Minister publicly called for a ‘credible and thorough’ international war crimes inquiry via the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC), citing the importance of independence in order to ‘[bring] justice and closure and healing’.

However, most recently, UK support for a strong international justice mechanism seems to have been diminishing, with the UK's present position being the support of a solely national 'political solution, mediated by the international community’.

Many do not feel as if this new position is good enough, given continued human rights abuses in Sri Lanka: the need for international participation, according to a

most recent UN report, is clear. How can the Sri Lankan people have faith in a purely national mechanism, when key witnesses still do not have access to proper protection and are afraid to speak out? How can a national tribunal convened by a government whose members are themselves implicated in the crimes be expected to hold the right people thoroughly to account?

As Siobhain's letter states: '

Six years after the end of the brutal civil war, not one person has been prosecuted for war crimes, despite the fact that forty thousand Tamils died in the final stages of war alone. We cannot stand by and let limited national mechanisms fail to provide the victims of inhumanity the fairness and justice that they truly deserve.

The justice process must have people’s full confidence if it is to bring closure and a new beginning for the Sri Lankan people.'

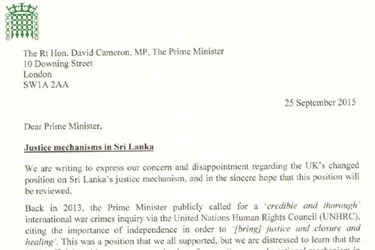

You can read the letter, sent to the Prime Minister, the Foreign Secretary, and the Minister of State (Hugo Swire) below:

Dear Prime Minister,

Justice mechanisms in Sri Lanka

We are writing to express our concern and disappointment regarding the UK’s changed position on Sri Lanka’s justice mechanism, and in the sincere hope that this position will be reviewed.

Back in 2013, the Prime Minister publicly called for a ‘credible and thorough’ international war crimes inquiry via the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC), citing the importance of independence in order to ‘[bring] justice and closure and healing’. This was a position that we all supported, but we are distressed to learn that the UK’s official position now seems to be that of supporting a purely national mechanism in Sri Lanka, according to remarks made by the Rt Hon. Hugo Swire MP, Minister of State at the Foreign Office.

As the Minister stated in the Westminster Debate on the subject on 15 September 2015; ‘Our expectation is that Sri Lanka will now take forward the [UNHRC] report’s recommendations… [The new government in Sri Lanka] has our full confidence… We need to understand that there has been a sea change in Sri Lanka. We need to get behind the new administration.’

There is no doubt that the election of President Sirisena represents a considerable improvement and renewed hope for the country. But this is no reason to pass all responsibility for justice to the national government, and we do not share the Minister’s overwhelming optimism.

Change in Sri Lanka is slow, and confidence in the state apparatus is very low amongst Tamils. Even more concerning is the recent report from Freedom From Torture, Tainted Peace (2015), which has shockingly found that torture, mainly of Tamils, has continued well into the new government. As the report notes, there has been limited action from the new administration to tackle vested interests in the military, police and intelligence services. Furthermore, President Sirisena himself served as Defence Minister in the final days of the civil war, when most civilian casualties occurred. Meanwhile, many of the most senior government and military figures remain unchanged from those dark days.

How can the Sri Lankan people have faith in a purely national mechanism, when key witnesses still do not have access to proper protection and are afraid to speak out? How can a national tribunal convened by a government whose members are themselves implicated in the crimes be expected to hold the right people thoroughly to account?

There is no evidence either that a national mechanism alone will enable justice truly to win through, or that the new government’s good intentions will be strong enough, or that the administration is competent enough, to act. Indeed, Sri Lanka is not itself a signatory of the Rome statute, which means that its laws do not cover a number of the international laws that were clearly breached during the civil war.

The Tamil people themselves therefore support a hybrid mechanism which incorporates both national and international involvement. This is reflected in the request for UK assistance made by the Chief Minister of the Northern Province in July 2015, in order to reach a ‘political solution, mediated by the international community’.

The UK is in a position of huge importance on this issue, and it therefore has a moral obligation to push for the course of action that really brings justice to the Sri Lankan people. We can assert a position where we express hope in the new government without suddenly releasing ourselves from our moral responsibility.

Indeed, as the UNHRC report states:

"The Council welcomes the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Report on Sri Lanka and fully endorses all the recommendations, especially creating a Hybrid Court with International Judges, Prosecutors and Investigators."

"The Council further urges the High Commissioner to submit a report in the March, June, and September 2016 Sessions of the UNHRC about the progress in setting up the Hybrid Court and Prosecutions."

The Minister of State has suggested Sri Lanka simply needs a ‘credible domestic mechanism that meets international standards’ (Westminster Hall, 15 September 2015), but we do not agree that this is enough. Instead, the need for a hybrid mechanism that combines the best of national and international action to achieve the mutual goal of justice for the Sri Lankan people is clear.

We sincerely hope the UK government will turn away from its ‘hands-off’ approach, to reassert the importance of international oversight, and to call explicitly for the full implementation of the UNHRC’s recommendations. Full justice and accountability requires not just the use of existing national mechanisms but full institutional reforms and international supervision to ensure these crimes can never happen again.

Six years after the end of the brutal civil war, not one person has been prosecuted for war crimes, despite the fact that forty thousand Tamils died in the final stages of war alone. We cannot stand by and let limited national mechanisms fail to provide the victims of inhumanity the fairness and justice that they truly deserve. The justice process must have people’s full confidence if it is to bring closure and a new beginning for the Sri Lankan people.

We look forward to these matters being taken into account and the UK’s position on this important subject being reviewed.

Yours sincerely,

Siobhain McDonagh MP

Senior Vice Chair of the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Tamils

Joan Ryan MP

Vice Chair of the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Tamils

Mike Gapes MP

Barry Gardiner MP

John Mann MP

Stephen Pound MP

Steve Reed MP

Virendra Sharma MP

Stephen Timms MP